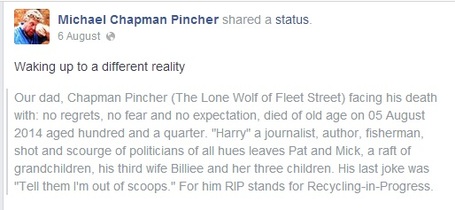

Farewell to a flawed hero of journalism, super-scoop Harry Chapman PincherThursday 7 August, 2014

Every business has its legends, the names that conjure up a forgotten era, inspire anecdote and vitriol, admiration and distaste. For a wannabe journalist growing up in the Sixties and learning the trade in the Seventies, John Pilger of the Mirror was the campaigning hero, the greatest reporter of all time, the righter of wrongs. James Cameron was the man who knew the world. Arthur Christiansen was the supreme editor. And Chapman Pincher was the man who knew all the Government's secrets. These were the freezing cold war years when Khrushchev outraged the world by banging his shoe on the table at the UN, when the youthful Castro played JFK for a fool at the Bay of Pigs, when a minister had to resign because he had slept with a woman who had also slept with a Russian spy. These were the years when John le Carré introduced us to George Smiley, Karla and Alex Leamas, the spy who all-too-briefly came in from the cold; when we learnt that secret agents were not debonair men in bow ties who liked their martinis shaken not stirred, that there were more unhappy than happy endings. And all the time Pincher was spelling out to us that these things happened in the real world. He knew all about Burgess, Maclean, Philby and Blunt; he exposed Klaus Fuchs, he outed the former MI6 chief Maurice Oldfield, he revealed the extent of George Blake's treachery; his stories scuppered an arms deal with Franco and enabled an H-bomb test off Christmas Island.

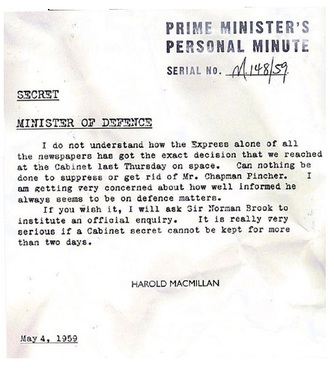

The latter was the result of printing a deliberate piece of misinformation. For while Pincher may have irritated Macmillan to the point where the Prime Minister sent a memo asking if the journalist could be got rid of (above), he was also a willing disseminator of information that others wanted out in the open. The historian E P Thompson's description in the New Statesman: The columns of the Daily Express are a kind of official urinal where high officials of MI5 and MI6 stand side by side patiently leaking.. has been widely quoted, and was apparently a source of delight for Pincher. But that isn't the complete quotation. There is a sting in the tail:

Mr Pincher is too self-important and light-witted to realise how often he is being used Pincher did realise that he was being used, but so long as he got the scoops and the bylines and the glory, that was fine by him. Thompson was, however, right that he was self-important and once he retired from day-to-day reporting, he made a handsome living publishing a stream of books and pronouncing on any and every spy scandal. But he was far from infallible - most notably in his hounding of Sir Roger Hollis, whom he was convinced was the "fifth man" in the Cambridge spy ring.

Great play has been made of his wonderful memory and the fact that he never took a note as he lured confidences from the great and not-so-good over expensive lunches, on the grouse moors, at the river's edge. It all sounds wonderfully romantic and old school, but we should beware of sighing and thinking "those were the days". How do we know his memory was reliable? Because he said it was. His stories were never challenged. Given the subject matter, a corruption of Mandy Rice Davies's riposte comes to mind: well they wouldn't would they? Pincher's death falls in a week that has seen the publication of three books about the phone hacking saga, exposing good and bad practices of modern investigative journalism. It comes in a year that has seen the Guardian garlanded at home and abroad for its Edward Snowden stories, echoing, if you will, Pincher's contacts and his scoops; reminding us that people in the secret services can and do use journalists to further their own agendas. How would his methods stand up to today's codes of conduct? Would he be celebrated for his exclusives or vilified for bugging restaurant tables? And would it even come to that? For what modern management would tolerate his huge expenses bills, his skiving off for long weekends in the country?

No matter how terrific the scoops, the money isn't there any more to indulge star writers to such an extent.

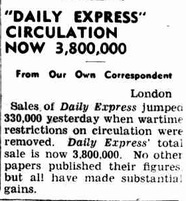

When Pincher joined the Express staff in July 1946 it was selling three and a half million copies a day. In September that year it was able to publish the little boast on the left. ABC figures for July, which have just been released, put the paper's daily sale at 480,668. This isn't because the paper has stopped printing stories about Soviet plots and started printing stories about house prices; it's because people have so many other sources of information that they don't need to buy a couple of dailies and an evening paper plus a local weekly. The readers don't have the money and nor do the proprietors. It takes a great leap of faith for any publisher to invest in investigative journalists and to give them the freedom they need to produce the goods. It is doubtful that any modern journalist will ever enjoy the access or liberty to match Pincher's prodigious catalogue of exclusives. And so while this ageing journalist recognises that Chapman Pincher may not have been quite the hero the wannabe imagined fifty years ago, she still mourns his passing and salutes him. Here's the man himself in an interview with Jon Snow for Channel 4 this year:

And here are some of his books, most available for a penny plus postage - or £4,000+ if you want a brand new copy:

|

|

Chapman Pincher:

the obituaries Today's papers have done Pincher proud with a clutch of readable obits. The Independent even has a little piece by Tam Dalyell. Here are the pages and links to the online versions Also worth

a read..

Pincher tells a good story, with persuasive dollops of coincidence as the evidence. None of it is as surprising, however, as the discovery that the author is still alive and has spent the past few years hunting through newly declassified documents and pinging off emails to retired KGB officers in Moscow

- Ian Jack The Guardian, 2011 |

Please sign up for SubScribe updates

(no spam, no more than one every week or two)

|

|

|