Smog coverage is as clear as yesterday

Friday 4 April, 2014

Thursday The Mirror is alarmist, the Telegraph confused, the Sun witty and the Times is in denial.

Everyone has a smog story. Unfortunately everyone has a different smog story, so whether you carry on as normal, put on a mask or stay indoors depends as much on which paper you read as your state of health and where you live.

Several papers run headings saying that people are being urged to stay indoors, but none says by whom or gives a direct quote. We do, however, have Professor Frank Kelly, chairman of the Health Department's air pollution committee, endorsing schools that decided to keep children indoors at breaktime, while one school governor notes "the absence of any formal advice from government".

There's a lot of mortality about: "killer smog", "deadly smog", "breath of death". Again, where is the evidence for this? Air pollution is thought to be responsible for about 60 deaths a week, so the likelihood is that people will die after this smog. But by that token every lawnmower, chainsaw or kitchen knife could be labelled a killer tool.

So far, so scary. Then along comes the Times with a "calm down, dear, what's all the fuss about?" approach. There's nothing wrong with a paper standing apart from the pack, in fact it is to be recommended, if it keeps common sense and science on its side and backs up the argument with facts. That way, the paper enriches the national debate.

This time, though, the Times seems to have been too dismissive. While most papers had a pollution picture on the front, the Times chose an American writer with her pet kangaroo. A paragraph in the teaser briefs points readers to Ben Webster's skinny page 9 lead headlined "Forecasters in blunder over air pollution".

Thursday The Mirror is alarmist, the Telegraph confused, the Sun witty and the Times is in denial.

Everyone has a smog story. Unfortunately everyone has a different smog story, so whether you carry on as normal, put on a mask or stay indoors depends as much on which paper you read as your state of health and where you live.

Several papers run headings saying that people are being urged to stay indoors, but none says by whom or gives a direct quote. We do, however, have Professor Frank Kelly, chairman of the Health Department's air pollution committee, endorsing schools that decided to keep children indoors at breaktime, while one school governor notes "the absence of any formal advice from government".

There's a lot of mortality about: "killer smog", "deadly smog", "breath of death". Again, where is the evidence for this? Air pollution is thought to be responsible for about 60 deaths a week, so the likelihood is that people will die after this smog. But by that token every lawnmower, chainsaw or kitchen knife could be labelled a killer tool.

So far, so scary. Then along comes the Times with a "calm down, dear, what's all the fuss about?" approach. There's nothing wrong with a paper standing apart from the pack, in fact it is to be recommended, if it keeps common sense and science on its side and backs up the argument with facts. That way, the paper enriches the national debate.

This time, though, the Times seems to have been too dismissive. While most papers had a pollution picture on the front, the Times chose an American writer with her pet kangaroo. A paragraph in the teaser briefs points readers to Ben Webster's skinny page 9 lead headlined "Forecasters in blunder over air pollution".

"The Met Office has admitted that it overstated the threat from air pollution yesterday and said that people had been panicked partly because it had just introduced a new forecasting system."

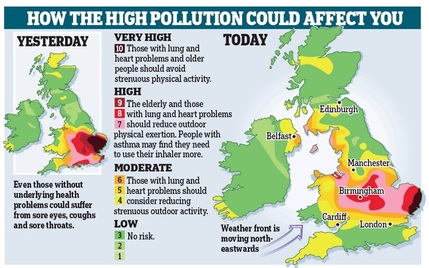

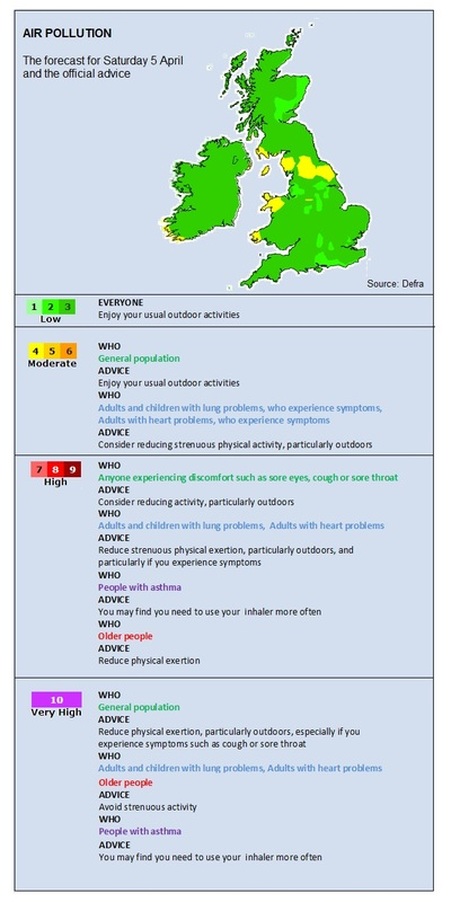

Webster goes on to say that high or very high levels of pollution were predicted for southern England and the Midlands, but that nowhere had reached the highest reading of 10 on Defra's index. Some parts of the East saw level 7, but for most of the country levels were low or moderate. The Independent and the Guardian beg to differ, both reporting that East Anglia hit 10 on the Defra index and was likely to do so again today.

No wonder the Telegraph is confused. It has one government department issuing alerts while Public Health England says most people won't notice any difference.

Most papers (apart from the Times) used graphics to explain the Defra index and show what air quality had been on Wednesday and what it was expected to be on Thursday. The Mail's (below) was probably the best, although it's a shame it didn't stick with the Defra colour scheme. The Independent and Express both presented the "yesterday" map as the "today" forecast.

Friday The Mail and the Express are spluttering, the Mirror is gasping, the Times gets with the programme and the Telegraph loses interest. Cameron decides not to go jogging, but Boris merrily cycles to work.

Again, everyone has a smog story. Millions are miserable, choking and wheezing. Emergency call-outs to people having trouble breathing are soaring. There's rather less death about, other than in the Star, but there's more toxicity, and even the Times talks about "danger levels".

Who are these millions of suffering people? The Mirror puts a precise figure on them: 1.6m. How come? It's simple arithmetic. Asthma UK conducted a spot survey among members, 30% said they had suffered an attack as a direct result of the pollution and 84% had used their inhalers more than usual.

Asthma UK has 5.4 million members, ergo 1.6m people had had attacks. The Express and Mail drew the same conclusion, although they refrained from giving a final tally (the Express wrote of "millions", the Mail "more than a million are feared to have...")

But surveys don't work like that. What the three tabs failed to mention was that the Asthma UK poll involved 532 members. So we know that 159 or 160 of them had attacks. It is not a reasonable extrapolation to take a sample of 1/10,000th of the organisation's membership and multiply it up; it will not give a reliable result.

Again, everyone has a smog story. Millions are miserable, choking and wheezing. Emergency call-outs to people having trouble breathing are soaring. There's rather less death about, other than in the Star, but there's more toxicity, and even the Times talks about "danger levels".

Who are these millions of suffering people? The Mirror puts a precise figure on them: 1.6m. How come? It's simple arithmetic. Asthma UK conducted a spot survey among members, 30% said they had suffered an attack as a direct result of the pollution and 84% had used their inhalers more than usual.

Asthma UK has 5.4 million members, ergo 1.6m people had had attacks. The Express and Mail drew the same conclusion, although they refrained from giving a final tally (the Express wrote of "millions", the Mail "more than a million are feared to have...")

But surveys don't work like that. What the three tabs failed to mention was that the Asthma UK poll involved 532 members. So we know that 159 or 160 of them had attacks. It is not a reasonable extrapolation to take a sample of 1/10,000th of the organisation's membership and multiply it up; it will not give a reliable result.

No one thinks the smog this week compares with that of December 1952 that killed thousands - or even with everyday Beijing. But it is making people physically and mentally uncomfortable, and is therefore a valid news story.

We've been told that it has been caused by a combination of Saharan sand, industrial pollution being wafted over from the Continent and our own pollution. We can't do much about the first two, but the discomfort this week has been enough to make us ask questions about the third.

The Times's initial indifference seems to have been based on the fact that the alarm was raised just as the Met Office took over responsibility for issuing pollution bulletins, giving them a higher profile. Wednesday's smog was not as bad as one three weeks ago; Britain could generally reckon to see a 10 on the Defra scale half a dozen times a year.

The difference this time is that people have noticed, people are talking about it, people are going to see their doctors because they are having trouble breathing. It could be what a former colleague used to call a "moment". A moment when people start to take the whole issue of pollution more seriously, a moment when pressure starts to build for action to be taken - a moment that should be seized by environment correspondents to force into print the statistics and arguments that never normally get a look in.

As Professor Timothy Baker of King's College London, told the Independent: "The Met Office has taken over and has been leading its TV forecasts with pollution. Overnight this has pushed public awareness of pollution up to unprecedented levels - the only time it came close was in the 2003 heatwave. I am very excited...because public awareness and engagement is the first step to getting action."

David Cameron didn't risk his jog yesterday morning (Freudian slip - I just typed 'job'), but nor was he going to risk suggesting that there was anything to worry about. "It is unpleasant and you can feel it in the air," he told the BBC. "I didn't go for my morning run. But it's a naturally occurring weather phenomenon. It sounds extraordinary, Saharan dust, but that is what it is."

Boris Johnson was also dismissive: "I cycled this morning and it seemed perfectly fine to me. I think we need to keep a sense of proportion."

Exactly. A sense of proportion. A sense of balance. The killer smog headlines don't help the debate, but nor did the apparent complacency of the Times yesterday. The paper was right to make clear that the smog wasn't unusual, but that doesn't make the pollution acceptable; the story was up and running - and it wasn't a story about Met Office blundering or people panicking (even though they did).

Today Ben Webster explains that the Defra index is made up of a number of elements and that there is more to the current smog than Saharan dust that we can see on our cars. The main concern, he says, is the concentration of PM2.5 particles, produced (among other things) by diesel and petrol fumes, which are more dangerous than the desert dust because they are smaller and so can more easily penetrate deep into the lungs or bloodstream.

An even more reader-friendly explanation was offered by David Derbyshire in the Mail yesterday, the most complete and balanced factbox published so far, which included the graphic shown above. You can read it by scrolling down this article.

In the meantime, SubScribe offers some random nuggets that may be illuminating.

We've been told that it has been caused by a combination of Saharan sand, industrial pollution being wafted over from the Continent and our own pollution. We can't do much about the first two, but the discomfort this week has been enough to make us ask questions about the third.

The Times's initial indifference seems to have been based on the fact that the alarm was raised just as the Met Office took over responsibility for issuing pollution bulletins, giving them a higher profile. Wednesday's smog was not as bad as one three weeks ago; Britain could generally reckon to see a 10 on the Defra scale half a dozen times a year.

The difference this time is that people have noticed, people are talking about it, people are going to see their doctors because they are having trouble breathing. It could be what a former colleague used to call a "moment". A moment when people start to take the whole issue of pollution more seriously, a moment when pressure starts to build for action to be taken - a moment that should be seized by environment correspondents to force into print the statistics and arguments that never normally get a look in.

As Professor Timothy Baker of King's College London, told the Independent: "The Met Office has taken over and has been leading its TV forecasts with pollution. Overnight this has pushed public awareness of pollution up to unprecedented levels - the only time it came close was in the 2003 heatwave. I am very excited...because public awareness and engagement is the first step to getting action."

David Cameron didn't risk his jog yesterday morning (Freudian slip - I just typed 'job'), but nor was he going to risk suggesting that there was anything to worry about. "It is unpleasant and you can feel it in the air," he told the BBC. "I didn't go for my morning run. But it's a naturally occurring weather phenomenon. It sounds extraordinary, Saharan dust, but that is what it is."

Boris Johnson was also dismissive: "I cycled this morning and it seemed perfectly fine to me. I think we need to keep a sense of proportion."

Exactly. A sense of proportion. A sense of balance. The killer smog headlines don't help the debate, but nor did the apparent complacency of the Times yesterday. The paper was right to make clear that the smog wasn't unusual, but that doesn't make the pollution acceptable; the story was up and running - and it wasn't a story about Met Office blundering or people panicking (even though they did).

Today Ben Webster explains that the Defra index is made up of a number of elements and that there is more to the current smog than Saharan dust that we can see on our cars. The main concern, he says, is the concentration of PM2.5 particles, produced (among other things) by diesel and petrol fumes, which are more dangerous than the desert dust because they are smaller and so can more easily penetrate deep into the lungs or bloodstream.

An even more reader-friendly explanation was offered by David Derbyshire in the Mail yesterday, the most complete and balanced factbox published so far, which included the graphic shown above. You can read it by scrolling down this article.

In the meantime, SubScribe offers some random nuggets that may be illuminating.

|

- The Clean Air Act was passed in 1956 in response to the "Great Smog". It has been updated twice since: in 1968 and 1993. The 1968 legislation was put forward by the publisher tyrant Robert Maxwell, who was Labour MP for Buckingham from 1964-70.

Please sign up for SubScribe updates

(no spam, no more than one every week or two)

|

|

|